Mixing Family and Nursing History

Context

Family and nursing historians might share the same data sources but will usually have different perspectives. Family historians want to 'fix' the family connections and so might be more interested in what further connections they can establish, or if the data supports connections they have already surmised. Nursing historians want to 'fix' the context in that they want to understand the circumstances of the events and how that might relate to nurses more generally who shared the same context. Of course there is a significant overlap, and there are historical methodologies like the prosopography Keiron used for his PhD which actually makes use of this overlap.

What we want to present here is an example of the crossover between family and nursing history, and also an example of the serendipitous nature of much of what we do.

The Starting Point

My wife Alison and I share our passion for family history with one of her Aunts who sent us this photograph of a family wedding. It was as we we working out all of the people in the picture and where they fitted into our tree that we saw the sister of the bride was an Army nurse! So Alison has Army nursing in her blood!

The marriage of Christina Brodie and Duncan Scouller (Highland Light Infantry) in Coupar Angus, Scotland in 1916

The nurse's story

Alison writes: Although there are many nurses and other health care professionals in my family, I thought that my brother and I were the only military nurses. You can imagine my surprise therefore when I was shown a copy of this photograph of a family wedding that took place in 1916, and there standing beside the bride was an Army nurse. I thought that to stand so near the bride, she must be a family member, and subsequent enquiry among older family members established that she was the bride’s youngest sister, and an older sister of my maternal grandfather, James Brodie, and was therefore my great aunt – her name being Margaret Kiellar Brodie. She was born in Coupar Angus, Scotland in 1885[1] being the third child of six born to James Brodie, my great grandfather and his wife Jane Anne, nee Kiellar. We were able to authenticate these details in 1999 when visiting the Scottish Records Office at Register House, Edinburgh. This is an important task to undertake when researching your family ancestors, as family members do not always recall details with accuracy, and ‘wishful linking’ often occurs!

Knowing she was an Army nurse, I examined the photograph more closely, and could just make out the ‘T’ brooches of the Territorial Force Nursing Service (TFNS) on her tippet. I also was aware that there were many records of the TFNS at the National Archives in Kew and I looked her up in the online index. Sadly, I drew a blank, as while there were nurses with the name of Brodie, there were none with her two first names. I imagined that hers must have been one the records destroyed by a fire. However, when visiting TNA to do research for my MA thesis, I took the opportunity to check the written register of Army nurses from the first world war, and to my delight, there was an entry for her. I discovered that her name in the online index had been misspelled as Broadie, and that was why I could not find her. I obtained a photocopy of her complete military record[2], and thus learned a little about her service during World War One. Sadly, many of the military records held at Kew were weeded in the 1920s and 1930s, and there is very little about her early service, for example, there is no application form for joining the TFNS, which would have given me information about her nurse training school and her job at the point she was mobilised for service. However, we do know from another form in her record that she was working as a private nurse in Edinburgh when she was mobilised for duty.

My family informed me that she trained as a nurse at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, but I have nothing to authenticate this. However, the census of 1891[1], and 1901[3] both record her as living in Edinburgh with a maternal aunt and uncle, so it is likely that she would have done her training in Edinburgh. The 1911 census records her as visiting the same uncle and aunt, and her profession as hospital nurse[4]. As far as I am aware she was the first person in my family to qualify as a nurse. In 1914 she joined the TFNS as a member of 1st Scottish General Hospital based in Aberdeen[2] which was one of four Territorial Force Hospitals established in Scotland. Margaret was mobilised for war service in October 1914, and served until she resigned from the TFNS In February 1919[2].

Start of military service

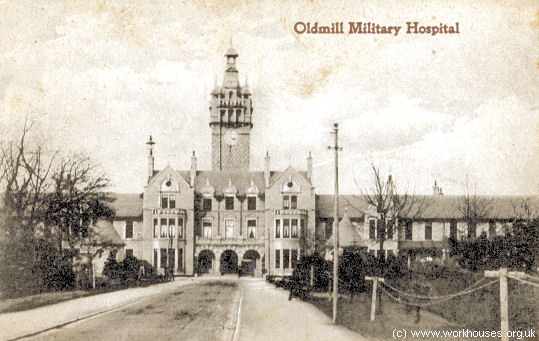

1st Scottish General Hospital had provision for nursing 34 officers and 1385 other ranks and was spread across several buildings in Aberdeen. These included the High School for Girls (now Harlaw Academy), The Central School (now Aberdeen Academy), and two other schools together with huts and tents. The buildings of Oldmill Poorhouse formed the main part of the hospital. Oldmill was built in 1902-3, and after the war it became Woodend General Hospital in 1927. It was also designated as a military hospital in world War 2[5].

The TFNS General Hospitals in WW1 were tasked to provide hospital services in the UK and members of the TFNS were not liable for service overseas as were QAIMNS and QAIMNS(R). We can assume therefore, in the absence of evidence to the contrary that Margaret spent the first two years of her service working at 1st Scottish General Hospital as a TFNS staff nurse. Later in the war, members of the TFNS were allowed to volunteer for overseas service, and this is what my great aunt did in 1916. Her record[6] shows that she was medically examined by Major TW Giddin, RAMC(T) on September 26 1916, and was found to be fit for active service. It was also confirmed that she was inoculated against typhoid and paratyphoid on 12 February 1916, and vaccinated (presumably smallpox vaccination) on April 8 1916.

Her annual confidential report written on 25 May 1916[6] makes interesting reading, being somewhat ambiguous in its content! Signed by her matron Miss E Philp, TFNS, it states “ Miss Margaret K Brodie has acted under me as staff nurse since 5 August 1915. I consider her professional ability equal to her standard of work and other qualifications, professional and moral as detailed above, quite satisfactory. General influence good except for a lack of dignity of demeanour noted…”. The counter–signatory to the report, Miss Edmondson, TFNS the principal matron, then writes “kindly explain ‘the lack of dignity’ noted”. Miss Philp’s response “the lack of dignity noted is entirely a matter of my own observation of Miss Brodie's bearing in the wards and about the hospital. I do not feel that her value as a good staff nurse is materially affected by it and I anticipate improvement”, is somewhat vague. The commanding officer is his comments notes that “her lack of demeanour has been reported to me by the MOs doing duty in her wards”. It makes me wonder what she did to deserve this kind of comment!

Going overseas

Clearly the report did not hold her back, as in October 1916, Margaret was posted for duty to Salonica[6]. This is an often ignored theatre of the First World War, but there was fierce fighting and major battles took place. "The British Government is understood to have undertaken to supply some of the medical needs of the revived Serbian army after its return from Corfu. This aid extended to 7,000 beds distributed amongst four General Hospitals (Nos. 36, 87, 38, and 41) and one Stationary Hospital (No. 33). The administrative position of these hospitals was difficult: the patients were Serbian soldiers only, the staff and rations were British, and the control, transport, and disposition of patients were in French hands. Two of these hospitals (Nos. 36 and 37) were placed at Vertekop, near the borders of Serbia, on the Monastir Road, and their situation, about 30 miles behind the line, permitted almost all the surgical work of the Serbian army, not overtaken by French, to pass through their hands.

No. 38 General Hospital was stationed 3 miles south of Salonika, and was the hospital farthest from the Serbian lines. As a result, this hospital, whose specialist staff had been drawn from Nos. 3 and 4 Scottish General Hospitals, was rather starved in a surgical sense, and received very few war wounds of importance"[7].

Margaret embarked from Southampton on 20 October 1916 and arrived in Salonica on 31 October. It is difficult to read the name of the ships in which she sailed, but it appears that part of her journey was on the Britannic – sister ship of the Titanic, built in Belfast and launched in 1914. The Britannic was converted to a hospital ship and records show that it left Southampton in late October 1916 for Mudros in the Aegean island of Lemnos. Sadly the Britannic hit a sea mine off Italy on 21 November 1916 and sank with the loss of 30 lives[8].

Margaret was posted to 42 General Hospital, which acted in support of the Serbian Army. There is nothing noted in her file[6] until 31 July 1917, when she was admitted to 43 General Hospital with a pyrexia – not yet diagnosed. Fevers were common causes of morbidity in the Mediterranean at this time. By 15 August 1916, Margaret had recovered sufficiently to be transferred to the Sick Sisters Convalescent Camp at 66 General Hospital and remained there until 1 September when she rejoined 42 General Hospital for duty. On 28 September she was sent to 38 General Hospital on temporary duty. On 23 October, Margaret lost nearly all her belongings when they were blown out of her tent during a storm. The 38 General Hospital war diary entry for 23 October states “A great storm came on this morning, the wind commencing to get high about 3am. Between 5 and 5.30 am it attained its maximum intensity. The greatest part of the hospital was blown down during this half hour. Only about 28 marquees were left standing”. Later that morning over 700 patients were accepted by neighbouring French hospitals, and this was followed by another 300 being sent the following day. 88 marquees were damaged, and re-erection was impeded by heavy rain and high winds. However, the rain stopped and the winds helped to dry off the tentage. The hospital was fully re-erected by 27 October[9].

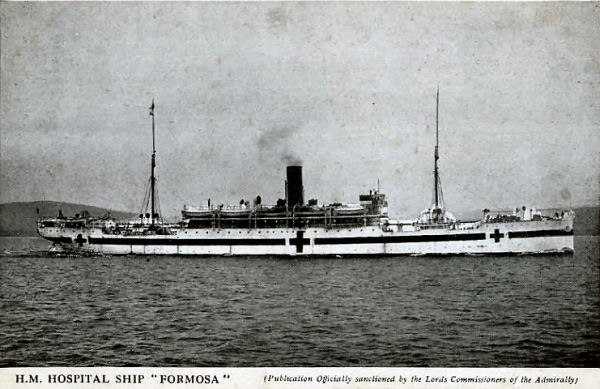

She didn’t stay long at 38 General Hospital, as on 1 November she embarked for duty on the Hospital Ship HMHS Formosa. This ship took casualties from the Salonica hospitals to Malta, a safer place for recovery. Miss A Beaumont, QAIMNSR, acting Matron of the Formosa reported on 2 December that Margaret was fit for general service; her conduct was excellent and she was a very good nurse and tactful with patients. Margaret wrote a letter to Miss Beaumont requesting permission to buy a new TFNS badge, as hers has been lost in the storm at 38 General Hospital and she had been unable to find it. Miss Beaumont forwarded Margaret’s letter to the Matron in Chief, TFNS, Dame Sidney Browne, enclosing a postal order for 2/9d (about 35 pence in today’s money) to pay for the new badge. Dame Sidney agreed to the issue of a new badge, and fortunately for Margaret, she did not have to pay for it as the loss was not her fault![6].

Returning home

At some point while she was journeying around the Mediterranean on the Formosa, or when it sailed back to UK, Margaret must have received a letter from home that she was needed, because on 7 January, 1918, she wrote to Miss Beaumont requesting two months leave for urgent family affairs[6]. Miss Beaumont agreed, and recommended two months leave be granted. This seems to be the start of a difficult time for Margaret who found herself torn between her duty to the TFNS and war effort, and her responsibility to her family.

Margaret found herself back in Coupar Angus on 9 January 1918, so it appears the Formosa had returned to the UK. At one point in mid-January Margaret was recalled from her leave to report back to the Formosa in Cardiff Docks. Margaret sent an urgent telegram to the War Office as it wasn’t clear if her leave had been formally sanctioned. However, she was allowed to remain on leave, and another TFNS sister was posted to the Formosa in her place. Towards the end of her leave a letter from Dame Sidney requested Margaret to report for duty at 1st Scottish General Hospital, Oldmill section, Aberdeen on 9 March 1918, and so her overseas tour of duty was over[6].

Margaret was clearly beginning to think about her future. In 1918, a Royal Air Force Nursing Service had been formed, and Margaret decided to apply to transfer to it. On 17 August 1918, she wrote to Miss Sinclair, TFNS, the Matron of 1 Scottish General Hospital requesting such a transfer, and her request was forwarded on to Dame Sidney at the War Office. A speedy reply from Dame Sidney dated 22 August advised Miss Sinclair that “Miss MK Brodie cannot be transferred as she is a mobilised member of the TFNS for the duration of the war effort”[6].

The war was coming to an end, and Margaret was once more at home on leave with her family in Coupar Angus. On 5 October the Brodie family doctor, John Lowe, wrote to her Matron, Miss Sinclair, that “Miss Brodie is reluctantly compelled to remain at home for the moment due to influenza in the house”. Margaret followed this up with a letter dated 8 October in which she requests further leave to remain with her family – “baby only came on Sunday and nurse has to go to another case. My sister has been very ill, but her doctor thinks she should be fairly well, so if I could have my week and another fortnight’s leave, I should esteem it a great favour”. Dame Sidney granted her this leave, but without pay and allowances[6].

However, by 5 November Margaret’s sister “has taken influenza, and my mother is not fit to do any nursing. I cannot possibly leave”. In this letter to Miss Sinclair, Margaret states that she thinks it would be better for her to resign on demobilisation as “my people seem to need me so often and it must be most unsatisfactory for you never to be able to count on my services”. Dame Sidney agreed to a further month’s leave without pay and allowances. On 15 December, Margaret completed a resignation form.

The resignation was to come into effect on her demobilisation from active service, and Margaret wrote to Dame Sidney on 4 February 1919 requesting to be demobilised as soon as possible. In this she had the support of the Brodie family doctor, John Lowe, who wrote “I certify on soul and conscience that Mrs Brodie, Moray House, Coupar Angus is in delicate health and in consequence requires to be constantly taken care of by one of her daughters. None of them is available except Miss Margaret Brodie and it is absolutely necessary that she be allowed to return home in order to look after her mother”. Dame Sidney agreed to release Margaret before demobilisation “provided that it does not involve the appointment of another member”. Margaret ceased duty on 28 February 1919, and returned home[6]. She had served for four years and 48 days (the unpaid leave days did not count as service) and for her and many others, the war was over at last.

After the war

After the war, Margaret received a war gratuity, a sum of money granted to those who had served in the armed forces. She was allowed to keep her TFNS tippet medal as she had four years good service, and was awarded the British War Medal and Victory Medal in recognition of her services. On 31 March 1920, one year after she was demobilised Dame Sidney wrote a letter of thanks to Margaret. “I wish to take this opportunity to thank you for the good service you have rendered during the war. You work has been excellent and it has been fully appreciated by those under whom you have served. I wish you all happiness and success in your new life”[6].

Margaret’s new life was to be in South Africa. The last entry in her army file is a letter dated 27 April 1921 from the Overseas Settlement Office, Women’s Section, to Dame Maud McCarthy, the new Matron in Chief of the TFNS. “A warrant book has been issued to Miss MK Brodie for a free passage to South Africa sailing by SS Norman on 6 May 1921”[2]. I know little of Margaret’s new life in South Africa, although I recall my mother saying she was a hospital Matron and we received Christmas cards every year postmarked Knysna, South Africa.

The last chapter

In 1967 Margaret was in Scotland again. Whether she was visiting or had returned for good, I don’t know. I never met Margaret, and sadly she died, together with her sister, Christina, as the result of a road traffic accident in Bridge of Allan in 1967[10]. She is buried in the Brodie family plot in the graveyard of Coupar Angus Abbey, and is remembered together with other family members on a memorial stone. I was able to visit her grave with one of my sisters in 2013.

When I first looked at her army record, I felt that it did not say much about Margaret, but having read it in detail, I feel I got to know a lot about her through her letters to TFNS matrons, and by her confidential reports. Her letters requesting special leave, backed up by those from the Brodie family doctor explaining the circumstances at home, give us a picture of a young woman torn between responsibility to her family and duty to her country. In the end she chose family, but her independent spirit gave her a new life in South Africa for over forty years. Her ordinary story must be typical of many military nurses in the First World War, but it has been an inspiration.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Scotland Census 1891: Edinburgh St Cuthberts; ED: 86; Page: 8; Line: 10; Roll: CSSCT1891_352

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 The National Archives: War Office 399/ 10016 Broadie, Margaret

- ↑ Scotland Census 1901: Edinburgh St Cuthberts; ED: 72; Page: 6; Line: 1; Roll: CSSCT1901_384

- ↑ Scotland Census 1911: Edinburgh St Cuthberts; 685/04 067/00 006

- ↑ Historic Scotland/Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historic Monuments of Scotland, HMS World War One Audit Project (GJB) 30 September 2013

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedwo399" - ↑ Patrick, J. (1920) The Surgical Service of the Salonika Army. The Glasgow Medical Journal. XCIV (1): p.21-42

- ↑ http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/shipprofiles/p/World-War-I-Hmhs-Britannic.htm

- ↑ The National Archives: War Office 95/4933 38 General Hospital War Diary

- ↑ Perthshire Advertiser, January 25th 1967, p1. Col.5&6