Reports of nurses serving in WW1

Context

In the Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Nursing Corps (QARANC) archives within the Museum of Military Medicine there is a collection of reports written by Army nurses in 1919. They were asked to write these and return them to Maud McCarthy, Matron-in-Chief, British Expeditionary Force in France & Flanders (BEF).

They had been requested by ‘The Women’s Work Sub- Committee’, part of the Imperial War Museum which had been set up in 1917. The reports were a reflection on their work, and the authors were chosen to give a range of contexts and experiences.

The Women's Work Sub Committee

The Imperial War Museum came into being in 1917 as both a memorial to and a place of record of every type of British and Commonwealth activity that took place during the Great War[1].The founders created a ‘Women’s Work Subcommittee’ under the charge of Agnes Conway. “The six female members included devoted suffragette turned war worker, Lady Priscilla Norman as Chairman, and Voluntary Aid Detachment worker Miss Agnes Ethel Conway as Honorary Secretary”[2]. Lady Norman had helped run a hospital in France in 1914, and Agnes Conway had assisted in the care of wounded Belgians[3].

Lady Norman was the daughter of the 1st Baron Aberconway and sister of the Liberal politicians Henry D McLaren and Francis McLaren. In 1907 she became the second wife of Sir Henry Norman, also a Liberal MP. She was an enthusiastic suffragist, though not a militant, and before the war held the post of Hon Treasurer of the Liberal Women’s Suffrage Union. When hostilities broke out in 1914, she and her husband ran a small voluntary hospital at Wimereux, in northern France. She was awarded a CBE for her war services.

Agnes Conway, born in London in 1885, came from a well-connected family; her father, Sir Martin Conway, was an art historian, politician, explorer and mountaineer. He was also a passionate collector, served as Trustee of both the Wallace Collection and the National Portrait Gallery, and became the first Director General of the Imperial War Museum when it was established in 1917. Agnes Conway studied history, Greek and archaeology at Newnham College, Cambridge and dedicated twenty-five years of her life to archaeology[4].

The committee’s main objective was the compilation of a thorough record of women’s wartime activities. They set about collecting material from women’s organisations and noteworthy individuals, assembling an archive of written material and also commissioned photographers to record women’s work.

Most of the collection, now known as the Women’s War Work Collection, was compiled by volunteer labour between 1917 and 19203. The collection was broad and tried to capture all aspects of women’s work in this period. Areas of interest included employment, the Army, benevolent organisations, the British Red Cross Society, food, land, relief funds and welfare[2]. The evidence in this collection demonstrates that what women did in the Great War was nearly everything.

In 1919 the committee approached the Army to get some written reports from nurses and VADs working in a variety of settings. In turn, Maud McCarthy, Matron-in-Chief in France & Flanders, sent out a letter to a number of individuals asking for reports. It is not clear how many people she sent letters too, nor whether the collection of reports in the Museum of Military Medicine[5] is the complete set of returns.

The QARANC Association Heritage & Chattels Committee researched each of these nurses, and their reports are reproduced here alongside their biographies. In order to place the reports in order here is a description of the chain of evacuation.

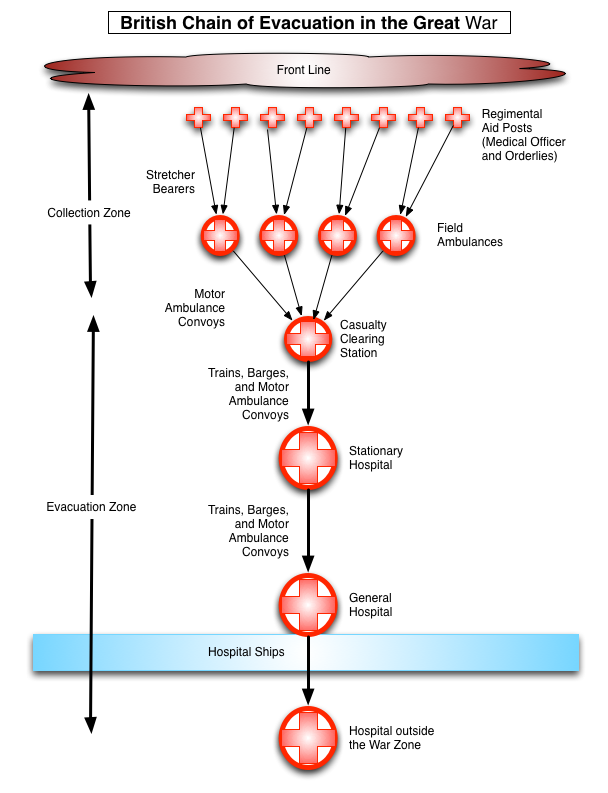

Chain of Evacuation

The First World War created major problems for the Army’s medical services. A man’s chances of survival depended on how quickly his wound was treated. In a conflict involving mass casualties, rapid evacuation of the wounded and early surgery was vital.

@Lt Col (Rtd) Keiron Spires QVRM TD

Regimental Aid Post (RAP)

The Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) chain of evacuation began at a rudimentary care point within 200-300 yards of the front line. Regimental Aid Posts were set up in small spaces such as communication trenches, ruined buildings, dug outs or a deep shell hole. The walking wounded struggled to make their way to these whilst more serious cases were carried by comrades or sometimes stretcher bearers. The RAP had no holding capacity and here, often in appalling conditions, wounds would be cleaned and dressed, pain relief administered and basic first aid given. The Regimental Medical Officer in charge was supplied with equipment such as anti-tetanus serum, bandages, field dressings, cotton wool, ointments and blankets by the Advance Dressing Station (ADS) as well as comforts such as brandy, cocoa and biscuits.

If possible, men were returned to their duties but the more seriously wounded were carried by RAMC stretcher bearers often over muddy and shell-pocked ground, and under shell fire, to the ADS, sometimes via a Collecting Post or Relay Post to avoid congestion.

Advanced Dressing Station (ADS)

These were set up and run as part of the Field Ambulances and would be sited about four hundred yards behind the RAPs in ruined buildings, underground dug outs and bunkers, in fact anywhere that offered some protection from shellfire and air attack. The ADS did not have holding capacity and though better equipped than the RAPs could still only provide limited medical care. Here the sick and wounded were further treated so that they could be returned to their units or, alternatively, were taken by horse drawn or motor transport to a Field Ambulance Main Dressing Station. The Main Dressing Station (MDS) roughly one mile further back did not at first have a surgical capacity but did carry a surgeon’s roll of instruments and sterilisers for life saving operations only.

In times of heavy fighting the ADS could be overwhelmed by the volume of casualties arriving and often wounded men had to lie in the open on stretchers until seen to.

Field Ambulance (Fd Amb)

These were mobile front-line medical units for treating the wounded before they were transferred to a Casualty Clearing Station. Each Army Division would have three Fd Ambs which were made up of ten officers and 224 men and were divided into three sections which in turn comprised stretcher-bearers, an operating tent, tented wards, nursing orderlies, cookhouse, washrooms and a horse drawn or motor ambulance. They did not deploy as a complete unit but as an ADS and an MDS. Later in the war fully equipped surgical teams were attached to the Fd Ambs and urgent surgical intervention could be performed to sustain life. By the autumn of 1915 some Fd Ambs had trained nurses posted to them.

In these early stages, men were assessed and then labelled with information about their injury and treatments. As in a Casualty Clearing Station, medical officers had to prioritize using a procedure known as triage. Many of the wounded were beyond help; morphia and other pain killing drugs were the only treatment.

Casualty Clearing Station (CCS)

These were the next step in the evacuation chain situated several miles behind the front line usually near railway lines and waterways so that the wounded could be evacuated easily to base hospitals. A CCS often had to move at short notice as the front line changed and although some were situated in permanent buildings such as schools, convents, factories or sheds many consisted of large areas of tents, marquees and wooden huts often covering half a square mile. Facilities included medical and surgical wards, operating theatres, dispensary, medical stores, kitchens, sanitation, incineration plant, mortuary, ablution and sleeping quarters for the nurses, officers and soldiers of the unit. There were six mobile X-ray units serving in the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and these were sent to assist the CCSs during the great battles. CCSs were often dangerously vulnerable with large depots containing munitions and supplies located alongside them, and which were targeted by enemy aircraft and artillery.

A CCS would normally accommodate a minimum of fifty beds and 150 stretchers and could cater for 200 or more wounded and sick at any one time. Later in the war a CCS would be able to take in more than 500 and up to 1000 when under pressure. In normal circumstances the team would consist of seven medical officers, one quartermaster and 77 other ranks, a dentist, pathologist, seven QAIMNS/ QAIMNSR/ TFNS nurses and other non-medical personnel. Major surgical operations were possible but sadly, men who had survived this far often succumbed to infection. The CCSs were usually in small groups of two or three to enable flexibility: one might treat cases for evacuation by train, ambulance or waterways to the base area, leaving one free to receive new casualties and another was able to treat the sick who could be moved in order to receive battle casualties in an emergency.

Initially the wounded were transported to the CCS in horse-drawn ambulances – a painful journey, and over time motor vehicles or even a narrow-gauge railway were used. Often the wounded poured in under dreadful conditions, the stretchers being placed on the floor in rows with barely room to stand between them. The admissions and evacuations were incessant and almost all that could be done in the time was to feed the patient and dress his wounds. One of the greatest boons was the provision early in 1915 of trestles on which the stretchers were placed. Comforts such as sheets, pillowcases and bed socks were obtained from such organisations as the British Red Cross Society. As the number of casualties grew so the need for experienced staff increased. In the first Battle of Ypres difficulties were highlighted with an influx of between 1,200 and 1,500 casualties in twenty-four hours and in the Battle of the Somme of July 1916 there were between 16,000 and 20,000 casualties on the first day of the offensive. By August 1916 selected CCSs had as many as twenty-five nurses on the staff.

Gas was first used as a weapon at Ypres in April 1915 and thereafter as a weapon on both sides. Patients were brought into the CCS suffering from the effects and poisoning of chlorine, phosgene and mustard gas among others.

The seriousness of many wounds and infection challenged the facilities of the CCSs and as a result their positions are marked today by military cemeteries.

From the CCS men were transported en masse in ambulance trains, road convoys or by canal barges to the large base hospitals near the French coast or to a hospital ship heading for England.

Ambulance Train

These trains transported the wounded from the CCSs to base hospitals near or at one of the channel ports. In 1914 some trains were composed of old French trucks and often the wounded men lay on straw without heating and conditions were primitive. Others were French passenger trains which were later fitted out as mobile hospitals with operating theatres, bunk beds and a full complement of QAIMNS/ QAIMNSR/ TFNS nurses, RAMC doctors and surgeons and RAMC medical orderlies. Emergency operations would be performed despite the movement of the train, the cramped conditions and poor lighting. Hospital carriages were also manufactured and fitted out in England and shipped to France.

In the early trains there was often a lack of passage between the coaches and with only a few nurses it was necessary for a nursing sister to pass from coach to coach, whether the train was in motion or not, usually carrying a load of dressings, medicines etc. on her back in order to tend to the wounded on each coach. During the night she also had a hurricane lamp suspended from her arm. The medical staff consisted of three medical officers of the RAMC including the Commanding Officer, usually a major, two lieutenants, a nursing staff of three or four with a Sister taking on supervision of the whole train, complemented by 40 RAMC other ranks and non-commissioned officers (NCOs).

An average load was 4-500 patients with a large number in critical condition. Often they were transferred to the train still in full uniform in shocking condition caked with mud and blood and owing to the cramped conditions their uniforms had to be cut away. Many journeys were long such as the one from Braisne to Rouen taking at least two and a half days. There were deaths on all journeys. The nurses’ workload was heavy, and they worked under dangerous conditions with the barest necessities and no comforts.

Hospital Barges

Many wounded were transported by water in hospital barges. Although slow, the journey was smooth, and this time allowed the wounded to rest and recuperate. The barges were converted from a range of general use barges such as coal or cargo barges. The holds were converted to 30 bed hospital wards and nurses’ accommodation. They were heated by two stoves and provided with electric lighting which would have to be turned off at night to avoid being an easy target for German pilots. Nurses would have to make their rounds in pitch dark using a small torch. Outside the barges were painted grey with a large red cross on each side with the flag poles flying the Red Cross to signify they were carrying wounded soldiers. The interior was painted white with ventilators in the side roofs and later skylights built in to the barge. There would normally be at least one QAIMNS/ QAIMNSR/ TFNS Sister, a Staff Nurse and RAMC orderly per barge but with a full load of patients an RAMC Sergeant, Corporal, three nursing Sisters, two orderlies, a cook & cook’s assistant. The skipper of each barge was usually a Royal Engineer Sergeant and the barge would be towed by steam tugs.

As the war progressed many soldiers were evacuated straight onto the barges from the trenches and battlefield and were ridden with lice and filthy. Due to the lack of ventilation there were problems with gas attacked patients with the smell of gas remaining on their clothing and breath which caused sickness, sore eyes and breathing problems to the nurses and patients.

Stationary Hospitals, General Hospitals and Base Area

Under the RAMC were two categories of base hospital serving the wounded from the Western Front.

There were two Stationary Hospitals to every Division and despite their name they were moved at times, each one designed to hold 400 casualties, and sometimes specialising in for instance the sick, gas victims, neurasthenia cases and epidemics. They normally occupied civilian hospitals in large cities and towns but were equipped for field work if necessary.

The General Hospitals were located near railway lines to facilitate movement of casualties from the CCSs on to the coastal ports. Large numbers were concentrated at Boulogne and Étaples. Grand hotels and other large buildings such as casinos were requisitioned but other hospitals were collections of huts, hastily constructed on open ground, with tents added as required, expanding capacity from 700 to 1,200 beds. At first there was a lack of basic facilities – no hot water, no taps, no sinks, no gas stoves and limited wash bowls. The staff establishment was normally thirty-four medical officers of the RAMC, seventy two nurses and 200 auxiliary RAMC troops.

Some general hospitals were Voluntary Hospitals supplied by voluntary organisations, notably the Red Cross and St John’s Combined Organisation who ran one at Étaples. In the base areas such as Étaples, Boulogne, Rouen, Le Havre and Paris, the general hospitals operated almost in the same way as civilian hospitals in the UK, with X-ray units, bacteriological laboratories etc. The holding capacity was such that a patient could remain until fit to be returned to his unit or sent across the channel in Hospital Ships for specialist treatment or discharge from the forces. Some of the general hospitals were handling the treatment of patients until well into 1919; in March 1920 there were still four active medical units in France – one General Hospital, one Stationary and two CCSs.

Hospital Ships and Military and War Hospitals at home

Most hospital ships were requisitioned and converted passenger liners. Despite the excellent nursing and medical care many patients died aboard because of their extreme wounds. The risk of torpedoes and mines as they crossed the channel was very real.

On arrival at a British port the wounded were transferred to a home service ambulance train and on to Military and War Hospitals which were divided into nine Command areas.

Note

Not included are numerous people and organisations who were also involved in the evacuation chain. The nursing staff were supplemented by trained nurses and by volunteers of the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VADs). The VADs worked in the general hospitals and in the last two years of the war in stationary hospitals. In the early days of the war there was a Red Cross train and No.16 Ambulance Train was staffed by the Friends Ambulance Unit. The VADs with trained Red Cross nurses were also employed right through the war on many railway stations and provided food, drinks, comforts and some first aid facilities.

Explanation of the chain of evacuation and treatment of wounded soldiers during the Great War – guest article by Caroline Stevens, Editor of Unknown Warriors: The Letters of Kate Luard, RRC and Bar, Nursing Sister in France 1914-1918

The Reports

- Casualty Clearing Stations

- Alice Duncan (Alice's Report)

- Dorothy Foster (Dorothy's Report)

- Kate Luard

- Katherine Skinner

- Hospital Barge

- Millicent Peterkin

- Hospital Trains

- Jessie Connal

- Kathleen Flower

- Laura James

- Janet Orchardson

- M Philips

- Stationary Hospitals

- Sybil Stratton

- Annie Plimsaul (Annie's Report)

- General Hospitals

- Christina Davidson

- Officers Hospitals

- Emma Dodd

- Eva Fox

- Adelaide Walker

- Base Hospitals

- Kathleen Barrow

- Lucy Card

- Gladys Howe

- Maud Hopton

- Evelyn Killery

- Una Lee

- Hospital Ship

- Alice Meldrum

References

- ↑ Paterson, S. (2018). “An Unusual Phenomenon”: The Women’s Work Sub-Committee at the Imperial War Museum and how it Recorded what Women Did during the Great War. Collections, 14(4), 533–546. https://doi.org/10.1177/155019061801400408

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mercer, A (2013): The Changing Face of Exhibiting Women’s Wartime Work at the Imperial War Museum, Women’s History Review, DOI:10.1080/09612025.2012.726119

- ↑ Grayzel, S. (2002) Women and the First World War. Harlow England: Pearson Education Limited

- ↑ Thornton, A. (2011) The Allure of Archaeology: Agnes Conway and Jane Harrison at Newnham College, 1903–1907. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, 21(1), pp.37–56. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/bha.2114

- ↑ Museum of Military Medicine, QARANC Collection, 43/1985.12.1 to 43/1985.12.29