Society Butterflies

=Context

The majority of the society ladies arriving in South Africa were seen as a nuisance by the nursing and medical staff, as seen in this letter to the press from an Army nurse[1]:

“The ‘lady amateur’ crops up everywhere when military excitement is going on. Lord Kitchener himself took most stringent measures to keep her out of the Soudan but she has succeeded beyond all precedent in this South African campaign. The ‘society ladies’ who shipped as nurses — many of them thus escaped paying their own passages — all wear silk gowns and the flimsiest caps and aprons, and look like the ‘nurses’ of fancy fairs. If amateurs came as ‘additional’ nurses they could play around brow-smoothing, and not do much harm; but in many instances the War Office authorises only a certain number of nurses in hospitals and transports. When society women, with no technical training, take these posts they fill posts which ought to be filled by certificated nurses. Real nurses, as consequence, are too few in number and terribly overworked by doing their own and the amateurs’ duties. No end of trouble has been caused these masquerade nurses to doctors, nurses, and poor, sick, wounded Tommies. They get in everybody’s way, and have no intention of working. Their idea is to take posts of authority and ‘boss’ the trained nurses who have borne the heat and burden of many years in hospital. We don’t grudge them going round the wards in fancy dress, distributing flowers, and petting Tommy Atkins. They can do this picturesquely enough. But interference with the nursing of the sick soldier is too serious a matter. Many of these amateurs were actually sent to the front. ‘Somebody’ in authority had the courage to send several of them back to the headquarters responsible for their appointment. Social influence has no right to count when it comes to war nursing. It would astonish English people did they know how many of these ‘nurses’, without one day’s hospital training in their lives, are trying their ‘prentice hands on Tommy sick. And if ever patients called for good nursing it is these poor fellows from the front—with terribly shattered wounds, enteric, and dysentery”

Sir Frederick Treves

Sir Frederick Treves gave a famous speech on his return to London where he described “the plague of women”. There was an outcry over this until he explained his position more clearly in the newspapers. This extract from the Pall Mall Gazette makes very clear the issues caused by the phenomenon of these visitors from the United Kingdom[2]:

“… That however, was not the worst side of their presence. When dinner parties and other junketing grew wearisome, they would make up parties to visit the hospital. ‘What shall we do today?’ ‘Oh let’s go and see the wounded’ would be the preparation to an invasion of the base hospitals and an incredible amount of interference with the work of the medical staff. Officers in charge of wounded would, in the course of their duties, be interrupted by ladies bearing permits signed by personages whose requests the officers dared not or did not care to refuse. You know perhaps, what influence means in the matter of promotion, and so the women would be taken round the wards and shown the wounded to the utter disorganisation of discipline and duty. There were cases in which the wounded men, aroused half a dozen times in succession by these meddlesome intruders, turned from them at last saying ‘Good Heavens, shall I ever get any peace?’ …”

The Hospitals

One of the advantages of the site of the Imperial Yeomanry hospital at Deelfontein was seen as its isolation and lack of accommodation nearby for potential visitors. Mr Alfred Fripp, the Assistant-Surgeon from Guy’s Hospital who was the Chief Surgeon to this branch of the Imperial Yeomanry Hospital, wrote[3]:

“We enjoy an immunity from outside interference which will be readily appreciated by all those who are in a position to realise what an amount of hard work has to be got out of the staff, and how easily the harmonious working of a large volunteer staff, such as ours is, could be upset, or at least hampered, by the existence in our neighbourhood of any factors capable of still further complicating the many interests which have to be considered in the running of such a hospital. Not a few ladies devoted to good works, but possessing no technical training, have come out to South Africa on purpose to ‘help in any capacity’ in the military hospitals, but the explicit instructions we have received from the Committee in London for whom we act, no less than the fact that there is not a room which they could hire for their accommodation within twenty-nine miles of us, has saved us from the unpleasant duty which might otherwise upon us of telling these willing but unwanted souls that after considerable experience of the value of their kindly meant offers, and after the fullest consideration, we would rather have their room than their company.”

Some of these ladies were very critical of the nursing and medical care given to soldiers without understanding the context in which this care took place[4] [5]. Lady Sykes gave this view of Army nursing[6]:

“As nursing is usually a profession embraced by those of the female sex who have not succeeded in becoming wives and mothers, my impression is that they are naturally sour and unsympathetic towards their patients, and that male orderlies are in every sense preferred by the sick and wounded soldiers, and are better suited to their work. Again, nineteen-twentieths of the professional nurses I have met are thin, angular, delicate beings, who require almost as much care as the patients. Besides … no unmarried woman understands or knows anything about a man, and, consequently, the poor fellows in hospitals were subjected to a system of discipline which prevented them from talking or smoking”.

Tatton Sykes, 5th baronet, was born in 1826. He married Christina Anne Jessica Cavendish-Bentinck who was thirty years his junior. Their marriage was a disaster and the coldness of their relations caused a rift that deepened with the passing years. By the 1890s Jessica Sykes was leading a gay but fragile (and alcoholic) life in London and was one of the ‘society butterflies’ who travelled to South Africa. She fell further and further into debt and disgrace culminating in Tatton Sykes refusing to pay her debts followed by a very spectacular court case. She died prematurely in 1912[7].

The previous chapter clearly demonstrated the professional nature of the nursing workforce in South Africa, and the selection process to ensure they were trained to acceptable standards. Evidence from soldiers writing home, civilians and military medical staff, and from official sources like the Royal Commission vindicated the nurses deployed in South Africa. When the Royal Commission[8] reviewed the failings of the medical support to British and Empire forces, they found that there was a need for more nurses and a better organisation[9]. They recognised that nurses had been striving to provide an environment to combat disease and prevent cross infection, but had been foiled by bureaucracy and the poor training of both soldiers and orderlies. This had been compounded by a number of logistical difficulties: medical and nursing support for this scale of warfare had not been planned for; there was a lack of trained (militarily and clinically) medical or nursing reserves; medical supplies came into South Africa via sea and rail with combat supplies always taking priority; and, the logistic chain had a lack of understanding of nursing needs. The difficulty with organising and deploying such a large hospital network and nursing workforce was highlighted by Mrs Chamberlain, one of the ‘society ladies’ excluded from visiting Army hospitals.

Mrs Chamberlain was the sister-in-law of the then Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, she was also a close confidant of Alfred Milner, British High Commissioner in South Africa, and had been widowed shortly before the Boer War. She made her own way out to South Africa and on the ship’s manifest gave her occupation as nurse and had a military nurse’s uniform, which she wore to special events. The Nursing Record and Hospital World[10] recorded the evidence given by Mrs Chamberlain to the Royal Commission. In her evidence she catalogued the general mismanagement she had found. This included both administrative and clinical mismanagement. She had spent a great deal of money rectifying deficiencies and she had, along with other ladies, provided services to the patients for letter writing and posting, as well as supplying them with comforts such as cigarettes.

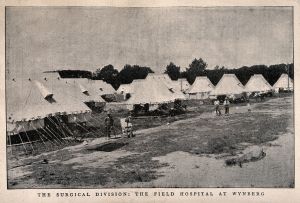

Although her account of the base hospital at Wynberg was refuted by the War Office, the nursing press had supported much of what she had stated on this occasion, and in her many letters to the general press.

Mrs Chamberlain was typical of well connected ladies who the medical officers in the hospitals found difficult to deal with. Medical officers were generally from middle-class backgrounds and so thought of as socially inferior by these ladies. The connections the ladies had, also made it difficult for the medical officers to control their activities, and there is no doubt that this caused a break down in the potentially useful relationships between these ladies and the hospitals. There were also many of these ladies near the base hospitals, and the sheer quantity of visits added to the confusion and chaos.

After they published one of Mrs Chamberlain’s letters, the Daily Express offered an opportunity of reply to the Army. The Army Medical Department’s view was that Mrs Chamberlain had taken it upon herself to alter the treatment of some of the patients and had ignored medical orders prohibiting certain foods. She had distributed comforts with disregard to the medical care of patients and had ignored orders given to her about when she might visit patients[11].

The accounts published by both Mrs Chamberlain and the Army Medical Department showed that although Mrs Chamberlain had the best of intentions in going to South Africa, she had set herself above the Army systems. In so doing she had created a situation, which ultimately led to her being sent home and excluded from South Africa.

That there was a problem with interference in nursing and medical matters is clear. It was an issue that eventually required a Royal solution. Queen Victoria took a keen interest in the Boer War and was regularly updated by reports from South Africa. She also followed the accounts in the newspapers. Many reports came back of the offence the ‘society butterflies’ were causing, and their interference in the work of the staff officers based in Cape Town, and also in the work of the hospitals nearby[12] [13]. Eventually she made her feelings known to her government, and Joseph Chamberlain sent a telegram to the governor of the Cape Colony in April 1900[14]:

“The Queen regrets to observe the large numbers of ladies now visiting and remaining in South Africa, often without imperative reasons, and strongly disapproves of the hysterical spirit which seems to influence some of them to go where they are not wanted. I conclude their presence interferes with work of civil and military officers.”

References

- ↑ A plague of women: Views of an Army nurse at the front (1900) Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser. Wednesday 09 May 1900, p7g

- ↑ The Plague of Women. Pall Mall Gazette; May 2, 1900: p.8a

- ↑ The Lady Hinderance in South Africa. British Medical Journal 1900;1:1423

- ↑ Sykes, J. (1900) Side lights on the war in South Africa. London: T. Fisher Unwin

- ↑ Brooke-Hunt, V. (1901) A Woman’s Memories of the War. London: James Nisbet & Co. Ltd

- ↑ The Plague of women at the front: Caustic remarks by Lady Sykes. (1900) Western Mail, June 3, 1900 p.6e

- ↑ Sykes, The visitors’ book, pp.36ff; Hobson, ‘Sledmere and the Sykes family’ [WWW] [1]

- ↑ Royal Commission (1901) The Care and Treatment of the Sick and Wounded during the South African Campaign. London: HMSO

- ↑ Schmitz, C. (2000) ‘We too were soldiers’: The experience of British Nurses in the Anglo Boer War, 1899-1902. IN: De Groot, GJ. & Pensiton-Bird, CM. (Eds) A Soldier and a Woman: Sexual Integration in the Military. London: Pearson

- ↑ Commentary. Nursing Record & Hospital World. Sep 22, 1900. pp.375-379

- ↑ Hearing both sides: Mrs R Chamberlain and the War Hospitals. Daily Express. Mar 7, 1900. p4e

- ↑ Menpes, M (1901) War Impressions: Being a Record in Colour. London: Charles Black N.D.

- ↑ Churchill, The Lady Randolph (1900) Letters from a Hospital Ship. Anglo-Saxon Review. Vol (V) June p.218

- ↑ Roberts, B. (1991) ‘Those Bloody Women’: Three Heroines of the Boer War. London, John Murray p.5